What do you know about Bhutan? Probably not very much, apart perhaps from it being a Himalayan kingdom somewhere up around Nepal and Tibet. Even now Bhutan is a remote and inaccessible corner of the world. There is no British embassy or other representation – the nearest consulate is in Kolkata (Calcutta) – all visits must be arranged through an accredited travel agency, and there are only two points of entry for foreigners (other than Indian nationals) – one by road and one by air. Only one scheduled air carrier, Druk Air, flies into Bhutan and the British Foreign Office advice to travellers says diplomatically, “We advise travellers who will be using Druk Air to build flexibility into their travel plans”.

What do you know about Bhutan? Probably not very much, apart perhaps from it being a Himalayan kingdom somewhere up around Nepal and Tibet. Even now Bhutan is a remote and inaccessible corner of the world. There is no British embassy or other representation – the nearest consulate is in Kolkata (Calcutta) – all visits must be arranged through an accredited travel agency, and there are only two points of entry for foreigners (other than Indian nationals) – one by road and one by air. Only one scheduled air carrier, Druk Air, flies into Bhutan and the British Foreign Office advice to travellers says diplomatically, “We advise travellers who will be using Druk Air to build flexibility into their travel plans”.

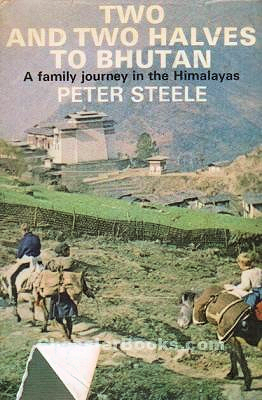

Back in 1967 this small country was even more isolated. Fewer than ten Europeans lived there. Much of the country was inaccessible to motor vehicles. Obtaining a visa was a time-consuming and uncertain bureaucratic nightmare and gave no guarantee either of admission or safe passage. Nevertheless, Peter Steele not only reached Bhutan but took his wife Sarah and their two children Adam, aged three and a half, and Judith, eighteen months. They became probably the first Westerners to achieve a complete crossing of the country.

At school in England Steele had been taught by Alfred Noyce, a member of the 1953 Hillary/Tenzing Everest expedition, and had met Eric Shipton on an Outward Bound course. Studying medicine at Cambridge he joined the university Mountaineering Club, and became an active climber and expeditioneer. After qualifying as a doctor in 1960 he went to work in Newfoundland, married Sarah (a nurse), and travelled with her overland to Kathmandhu where they worked in a hospital, climbed and trekked. He continued his involvement in remote community medicine when he took charge of the Grenfell Flying Doctor Service in Labrador for a year in 1964. On a trip to London the same year he was invited to meet the King of Bhutan to talk about the work he had done in Nepal and whether it might be possible to do similar work in Bhutan. At the meeting the King invited him to visit Bhutan. “You musn’t commit yourself to working in a country like Bhutan before you’ve seen what it’s like”, said the King. “When you find you’re free, come to Bhutan and bring your wife, as she must like it too.”

The trip didn’t happen for another three years, but in 1967 and now qualified as a surgeon Steele set off for Bhutan with a commission to study the incidence of thyroid goitre and to collect blood samples for the Serological Population Genetics Laboratory in the UK. Sarah, Adam and Judith were to follow a few weeks later.

The book itself is a straightforward account of their experiences. On their travels the children were mostly carried on horseback while the adults walked. They had with them an ayah (nanny) for the children, Lakpa, and a young “fixer” – officially interpreter and assistant – Chhimi, who had the advantage of being the son and nephew respectively of two important officials. Together they faced precipitous terrain, perilous river crossings, atrocious weather, and all the other hazards one would expect. Luckily the children had no problems with the strange and restricted diet, and although standards of hygeine had to lapse no major problems occurred.

Steele has not tried to enliven his account with amusing anecdotes or Palinesque asides, and although there are occasions when his dry humour shows through he mostly sticks to the facts. The book is therefore at its most interesting in giving a picture of Bhutanese life and society at that time – a picture drawn by an illustrator rather than an artist. If his account is restrained it is perhaps out of respect for his family and the people he met, many of whom became friends. We should remember too that the era of the amusing travel book had not yet arrived when this book was written (Bill Bryson was only 16 in 1967), and books of exploration generally kept to factual accounts and tended to be modest about how the authors coped in the face of adversity.

I don’t mean to impy the book is heavy or ponderous – it isn’t. My favorite lighter incident is when Steele has over a hundred blood samples to centrifuge – a heavy job with only manual equipment – and persuades a group of young Buddhist monks to use the centrifuge as a prayer wheel.

Steele pastes a few digressions into his story. There is a brief history of the country itself and the establishment of the ruling family. This will disillusion anyone who had a romantic view of Bhutan as some kind of peaceful, idyllic Shangri-La sheltered in its mountainous isolation. The truth (surprise!) is one of warlords, invasions, conquest and re-conquest, and more recently the playing out of the Great Game – the jostling for power in the region where the British Empire, China, and Russia (and now their successors) meet. The present ruling dynasty was established with sovereignty over the whole country in 1907, and given the turmoil that has gone on around them ever since can be said to have been remarkably successful.

In another section Steele explains in detail the hierarchy of government and administration in Bhutan, centred on the dzongs – buildings which “are the civic and religious centres of each region … [and] which physically and metaphorically dominate every aspect of life, temporal and spiritual, for persons of all strata in the society of Bhutan”. Here are explained the roles of the thrimpons and nyerchens; the gaps, the mundels, the dumpas and the cheupens; and the Dashos of high office. On the medical side, Steele discusses the ethical problems facing the travelling doctor, and explains the high incidence of goitre in some mountainous regions.

Although I might be accused of being unfair given what I said earlier about the established style of travel writing when Steele wrote this book, my overall feeling is slight disappointment. I would like to know more about the individual people, both the Steeles and the Bhutanese – more “human interest”. In particular I feel Steele let down the two main Bhutanese, Lakpa and Chhimi, who became part of the family and provided essential support throughout the trip. He pays them tribute at the end of the book:

“Chhimi and Lakpa had been part of our family – I say this without being patronising – they shared every experience and without them the success of our venture would surely not have been achieved.”

But that’s it. No account of their goodbyes, no indication of whether or not there was any further contact, not even a mention that they got back to their own homes safely. Strange. I wonder if Steele were to rewrite the book now he would do it differently. I wonder too if there is a hint of compromise in the statement at the front of the book: “The manuscript of this book has been corrected and approved for publication by His Majesty the King of Bhutan.”

There’s a brief story behind my reading “Two and Two Halves to Bhutan”. A companion on a mountain-walking holiday last year was a retired surgeon who knew Steele personally, told me about this account of his trip to Bhutan, and the title stuck in my mind. The book is currently out of print, but may be available second-hand.

Overall verdict: An interesting tale of hardships overcome in a country about which we know little

Hodder & Stoughton, 1970