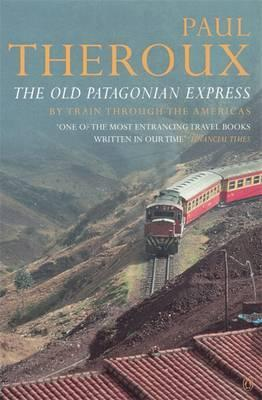

Theroux on a train – nothing original there. This is the second of his railway epics, and was many people’s introduction to the irrasicble American. From his home in Boston all the way down to Patagonia, Theroux undertakes the ultimate American (rail)road trip, and brings us all along for the ride.

Theroux on a train – nothing original there. This is the second of his railway epics, and was many people’s introduction to the irrasicble American. From his home in Boston all the way down to Patagonia, Theroux undertakes the ultimate American (rail)road trip, and brings us all along for the ride.

The narrative really picks up steam once Theroux leaves Texas – and his constant meteorological moanings – behind, and heads into Latin America and beyond. Those familiar with Theroux’s style (or who have read my review of Pillars of Hercules), will find much of his tone recognisable here. Often critical, but always engaging, this book has more consistent substance than Pillars. Some of the characters along the way assume almost legendary status, such as the guy who simply calls out the name of everything he sees, or the ubiquitous German tourist – the fact that it is a different German each time is oddly irrelevant.

One of the interesting sidebars to this book is the descriptions of Theroux’s reading matter on his travels. He takes us through each novel as he does through the countryside seen from the window. I love this part of Theroux’s writing; it lends an intimacy to the journey that can be hard to reach. And once aware of his love of literature, the climax of the book – where he reads to the blind Borges – is even more meaningful.

The section on Panama and the Canal Zone is particularly interesting. This was some 20 years before the US handed over control of the canal to the Panamanians in 1997, and yet that very transition was the main topic of conversation. It seems that Theroux dawdles in Panama, where he is entertained, and fêted, but for students of the side-effects of cold war geopolitics, this section is fascinating.

One of the strange aspects of this book is its timelessness. It is timeless in that no matter how often you read how long he has been away from home, you never get any sense of this being a long trip. Our ever-scribbling author covers such distances but then devotes lengthy sections to short periods of times, and whisks you through others. It is also timeless in the sense alluded to just above. This may have been written back in the late 1970s, but thanks to the immediacy of Theroux’s writing, and the global economic policies of the west, much of it reads as if it could have been written anytime in the last five years. I hope at least that Guatemala City has improved somewhat.

One of the best things about travelling with Theroux is that it is never comfortable. His disparaging remarks, his own endurances – such as the journey from Bolivia to Argentina on the Panamerican Express that arrived a day and a half late – and some of his travelling companions make for excellent vicarious reading. Theroux changed the benchmarks for travel writing, and in this early book he sets out his stall with conviction.

Don’t just read it for a fascinating insight into Central and South America, read it as a travel classic and Theroux on fine form.

Overall verdict: from Boston to Buenos Aires, you will not be bored.

Penguin, 1980

Good news, La Trochita, is back in service in Esquel:

The Old Patagonian Express Rides Again